There are about 700,000 people with dementia in the UK. Not all of them will, of course, be fortunate enough to have physiotherapy support. To ensure that practice is up-to-date and delivered in an appropriate evidence-based way, physiotherapists in County Durham have developed an illustrated set of rehab principles. Based on research evidence, it explains the physios’ specialist skills and role and what they can achieve.

Specialist mental health physios Jane Blakey and Rebecca Simpson from Auckland Park Hospital in Bishop Auckland, part of Tees, Esk and Wear Valleys NHS Trust, are behind the initiative.

Ms Blakey, a band 7 clinical lead, has worked at the mental health and learning disabilities trust for 13 years. She heads a team that includes specialist physiotherapists and a technical instructor. She explains that the principles outline suitable interventions, highlight best practice and aim to spread awareness about the benefits of rehab.

‘Often people just assume that because someone has dementia there is nothing you can do,’ Mrs Blakey says. ‘But it’s no different from other neurological conditions that are degenerative, in that if you concentrate on what is maintained or retained with the dementia process – rather than what is lost – there is a lot you can do with these patients.’

Principles behind the practice

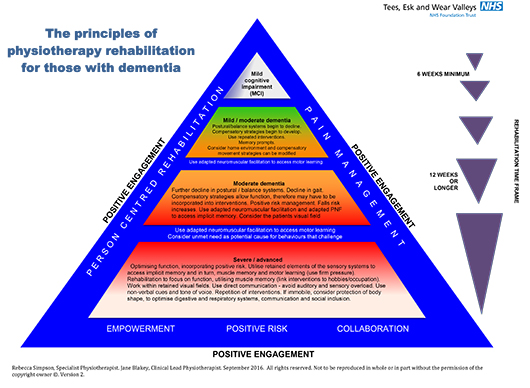

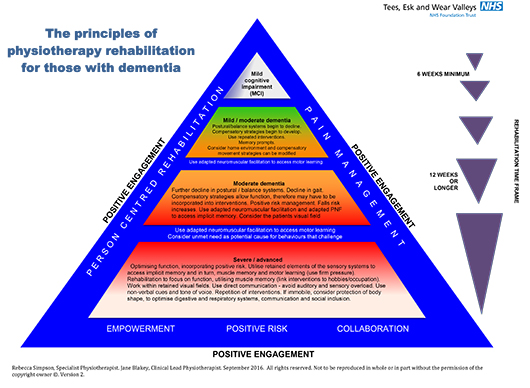

Their rehab principles are based on research based interventions that are appropriate to each patient and the stage of their condition. For instance, someone with moderate impairment may receive a 12-week treatment plan. Whereas someone with severe or advanced dementia may be given a much longer treatment period, allowing time for implicit muscle memory to develop.

Miss Simpson says: ‘We often get asked “Why are specialist mental health physios needed?” particularly for dementia. So the principles explain what we do and what makes us different.’

The team’s skills include Bobath training, specialist training from the Oxford Centre for enablement posture management for adults and children with complex disabilities. Other qualifications include the Northern Council for Further Education’s level 2 certificate in dementia awareness. ‘The right clinical skill set is needed to be able to adapt treatment techniques from one intervention to the next,’ says Miss Simpson. ‘Some of our patients don’t understand standard treatment prompts, so we have to use hands-on and non-verbal skills to get the best treatment outcomes.’

The team works on a specialist mental health inpatient ward, and in communities including Teesdale, Weardale and Sedgefield. Their daily caseload includes working on older people wards, providing physiotherapy clinics in the community and visiting patients at home, or in residential or nursing care settings.

Most patients with dementia are 65-plus, says Ms Blakey, and may have complex and multiple physical comorbidities. Referrals can come from the hospital’s inpatient wards, community mental health staff and a care home liaison team. ‘Length of stay on our inpatient wards can vary from 29 days to three months, depending on why they’ve been admitted,’ says Ms Simpson.

‘And patients coming to the community clinics tend to be those we see in care homes or their own homes, but feel could benefit from additional equipment that we can’t take out to them – such as a Bobath plinth, which is wider than a standard clinic plinth.’

Providing a suitable timeframe for the rehab is crucial, says Miss Simpson. ‘Access to physiotherapy in some services may be limited to six weeks, but often someone with dementia can’t reach their full potential in that timeframe.’ Ms Blakey explains that research studies show that effective rehab for people with dementia should be both long-term and high-intensity.

Muscle memory

The physios use many of the basic principles of Bobath, including adapted neuromuscular facilitation [activating a person’s implicit muscle memory].

‘We tap into muscle memory and normal movement patterns, but repeated interventions are needed and it takes a long time for implicit memory to start to develop,’ she says. ‘The research says you need to work with dementia patients for a minimum of eight weeks, and to get really good carry over you need 12 weeks for the muscle memory to take over and become automatic.’

Extra time is also required for assessing people with dementia, says Ms Blakey, and it can take several attempts to complete an assessment. ‘They may have receptive dysphasia, which mean they can’t understand what you’re telling them to do, or expressive dysphasia where they are not able to communicate with you verbally,’ she says. ‘Also, the degeneration within the brain effects memory and the ability to perform many tasks, so you have to simplify and pull everything back.’

In addition, it can take a while for a therapist to build up a rapport and gain the trust of someone with dementia, especially if they are not familiar with or fully aware of their environment. ‘With dementia there is a common misconception that it just affects memory,’ says Miss Simpson. ‘But global brain atrophy occurs with dementia, so as the process goes on people can lose specific movements, have visual impairments, difficulty swallowing, postural problems and hallucinations – so we have to work with all those as well.’

A person-centred approach

Due to the challenges they face the physios often find alternative ways of performing basic assessments, as well as treatment interventions. ‘One of the things that is often retained during the dementia process is rhythm,’ says Ms Blakey. ‘So we use a lot of rhythmical, repeated patterns and movements to try to initiate muscle memory.’ The team also looks for non-verbal social cues and gestures. ‘If you say “I really need to look at your walking today – can you stand up and come with me?” they might not understand that,’ says Ms Blakey. ‘But if you beckon them over and say “Would you like to come with me?” they may get up and walk and you can immediately start to assess them.’

A person-centred approach is also important, which includes taking each person’s social history and past occupation into consideration. ‘That worked quite effectively with one 92-year-old woman, who was in a care home and used to be a chorus line dancer,’ says Ms Blakey. ‘She’d had multiple falls and a significant head injury. So I found out a bit about her, introduced myself and started our conversation off by saying “I hear you used to be a dancer”.

‘All of a sudden she started to move her legs, which gave me an idea of what her functioning was. Then she took my hand and we had a bit of a dance. I had my hand on her trunk, so I could feel what was happening in her body and got a sense of how she was weight-bearing, and what she was avoiding doing because of pain. By doing that I managed to establish that she had lower back pain and we were able to treat that effectively, which stopped the falls.’

Ms Blakey and Miss Simpson hope that patients and staff at other NHS trusts may also benefit from their rehab principles. Their advice for physios who would like to emulate the model includes fostering a supportive multidisciplinary team environment and seeking support from like-minded professionals.

‘Have an open mind, be innovative and collate evidence with valid outcome measures,’ says Ms Blakey. ‘Provide the right intensity of treatment for the required length of time to achieve the best outcomes,’ adds Miss Simpson. ‘And focus on what is retained in the dementia process – not what is lost.’ fl

Resources

The 2009 National Dementia Strategy for England,

Living well with dementia, estimated that there were 700,000 people in the UK with dementia. And that figure is expected to rise to 1.4 million people by 2039, according to the Department of Health’s report.

Physiotherapy promotes and maintains the independence of people with dementia, according to guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. In addition, research shows that physiotherapy interventions can help to delay the progression of cognitive and functional decline associated with the condition (Verghese et al. 2003).

Agile, the CSP professional network for physiotherapists working with older people.

Author

Robert Millett