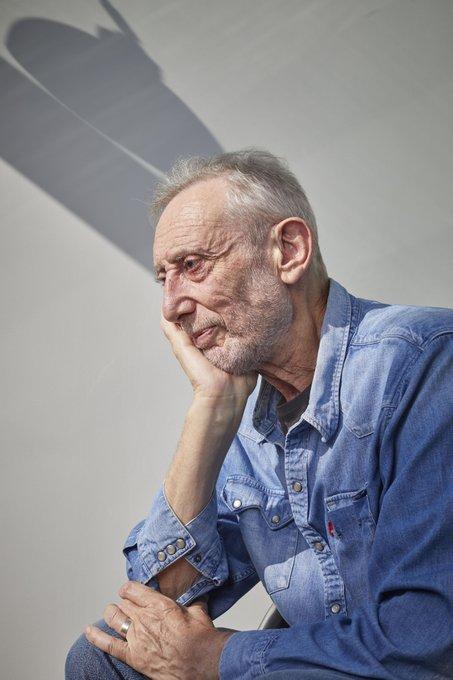

After being in a coma due to Covid, the author Michael Rosen required both inpatient and community rehabilitation to learn to stand and walk again. He credits his recovery to the care he received and spoke to Robert Millett about his rehab journey and the admiration he holds for the physiotherapists and other medical staff who helped him

In March 2020, the poet and children’s author Michael Rosen developed severe coronavirus symptoms and was admitted to the Whittington Hospital, in north London, where he was placed into an induced coma and spent the next six weeks unconscious and on a ventilator in intensive care.

Soon after he awoke, he was transferred to St Pancras Rehabilitation Unit, part of Central and North West London NHS Trust, where a multidisciplinary team, which included physiotherapists and OTs, helped him regain his mobility and learn to walk again.

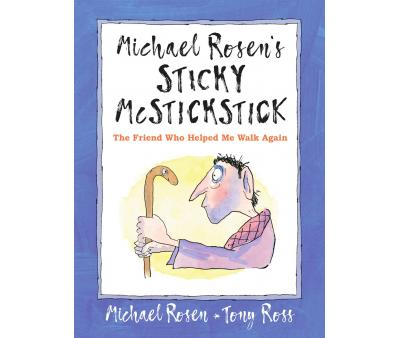

Following his recovery he wrote two books based on his experiences: “Many Different Kinds of Love: A story of life, death and the NHS ” for adult readers, which describes the care he received and everything that happened to him, and “Sticky McStickstick” for children, which humorously outlines his rehab journey and charmingly illustrates how he learnt to walk again.

Michael says both these books were a tribute to all the physios, occupational therapists and medical staff who helped him get better. He spoke to Frontline about his recovery, the rehab he received and the immense admiration he feels for all the physios and other healthcare professionals who helped get him back on his feet.

How did your illness begin?

I developed what felt like flu in the first few weeks of March 2020. And then Emma, my wife, noticed I was dipping and that I couldn’t breathe properly. We tried to get the ambulance service to come out. But they tested me, as it were, over the phone and reckoned that I didn’t have Covid and that my breathing was ok, although I was finding it difficult to breath. So in the end, Emma got in touch with a neighbour and a friend who’s a GP, and she came over with an oximeter.

And when they measured me, my oxygen level reading was 56. And, in the doctor’s words, she had never seen anybody conscious who had a reading as low as 56 – as it should be 95 plus. So I was obviously in a pretty bad state. So the doctor said, “Take him to hospital straight away. It’s really urgent”.

By then I was feeling a little bit woozy and didn’t know what was going on. So Emma took me to A&E and I was whisked into intensive care. I had one night there and apparently I revived somewhat, but then dipped again after a week. So they sedated me and I was in a coma for 40 days, and in intensive care for a total for 47 days.

It was a scary time – not for me obviously, because I was out of it - but I think it was scary for the practitioners as, on my ward, which was actually only equipped for 11 patients there were 24 of us, and 42 per cent of us died.

And no visitors were allowed at that time, due to Covid restrictions?

Yes. I don’t remember it, but the first time I saw my wife was round about day 44. After I woke up she was allowed in – but not to the ward. They arranged for me to meet her on one of the hospital atriums and apparently that was a game changer [for my recovery], because I recognised her and started talking sense after that.

Before that they were worried that I was stuck in a strange sort of delirium - a kind of interim state between unconsciousness and consciousness. So they were concerned I might have some brain damage, particularly as my left eye was dilated (and still is).

After you woke up and became fully conscious again, when did you become aware of the muscle wastage and deconditioning you’d experienced?

I think the first time I really understood it was when three guys came to my bedside and said, “We’re going to get you up”.

They swung my legs out of the bed and tried to get me to stand up. And I can just remember shaking like a leaf, absolutely shaking all over.

In no way could my legs support me. I had this image of myself having cardboard legs that were buckling.

So they had to support me and I was gasping in a rather horrible, raspy way – due to a mixture of panic and because I couldn’t control my diaphragm. I couldn’t bring it in, and I had very low blood pressure. It felt like I was drowning. So they quickly bunged me back into bed.

And then a couple of other physios came, and I think that was when they decided I needed the full physiotherapy available in a rehabilitation hospital.

Was it a confusing time for you, after you came out of the coma?

Yes. My wife would say to me “You were in a coma for 40 days”. And I just didn’t believe her. I thought, why is she saying this to me? And then a few days, she would say the same thing. “You were in a coma, Michael” And I would go: “Really?” I just couldn’t compute it.

I also thought that everything I was going through at the rehab hospital was because Covid had done the damage. I didn’t realise that it [the deconditioning] was mostly from intensive care.

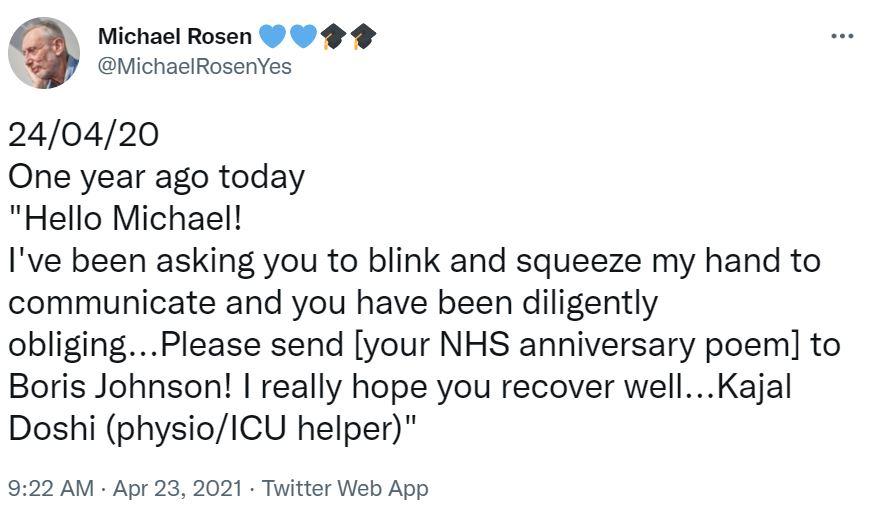

While you were in a coma the hospital staff kept a patient diary for you. Did those notes help you to understand what had happened?

Yes. The messages were all so amazing and personal and kind. There were about 40 -45 of these letters in the diary they made for me, just little notes from the nurses and therapists who were looking after me, and they wrote such beautiful letters, saying things like “We had to shave you today because we were worried about your tracheotomy scar getting infected” or explaining to me what a tracheotomy is and things like that.

Like this one about the songs my family sent: “Today, I’ve made you a playlist of all the songs your family sent us - some absolute tunes on there, you’ve been listening to the playlist all day. I think I’m enjoying it as much as you. We are going to video call your family shortly. It’s always important for recovery, to hear familiar voices. Keep fighting, I know you can do this!”

They wrote to me every day. And it’s just…it’s wonderful. It’s a wonderful thing. And it said on the cover that these diaries are written to help us relocate ourselves back in the real world.

Did the coma have any lasting effect on your memory?

Yes, it put me in this strange state of forgetfulness. To give you an idea of how forgetful I was, I was lying in bed in the hospital thinking, “I can’t remember what shoes I’ve got at home”. I had a pair of crocs in the hospital, you see, but I kept wondering, “What are my real shoes like?”, and I just couldn’t remember. They were gone from my brain.

And another time I said to my wife “When I get home I think it would be a good idea if I lived upstairs for a bit because I’d be nearer to the loo there.” And she said, “I don’t think you need to live upstairs.” I think she must have thought I’d gone nuts…I even had this fantasy about how we could convert the cupboard under the stairs into a downstairs loo.

Then, when I got home, I found that we already had a loo under the stairs! I said: “Emma, there’s a loo here!” and she went, “Yeah?” and I explained “That’s why I wanted to move in upstairs – because I’d forgotten we had a downstairs loo”. Even though it had been there since we moved into the house, it was completely gone from my brain. The coma had wiped it from my mind.

The coma was like some kind of black hole that had sucked in whole chunks of my memory

How did you find the rehab you received – and what did it involve?

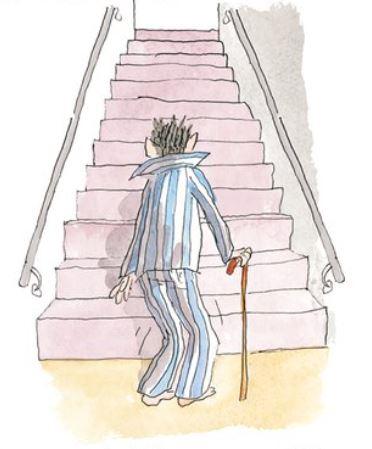

The very first thing was that they got me out of the bed and showed me how to grip a frame. And that seemed like an enormous thing at first – being able to stand, shaking, holding onto the frame. Then they showed me how to move with it, shunting it forwards.

And all the time they gave very careful instructions, like these little chants that get into your head “Lift and step and lift and step” and things like that. And the moment I mastered that I thought “Oh, ok, I guess I’m Zimmer frame person from now on”.

But then, before I knew it, they said: “Now we are going to get you into a wheelchair”. And I thought, “Wow, that’s incredible”.

So they showed me how to get from the Zimmer to the wheelchair. They’d line it up, get the angles all right and then I’d sneak my bum into it and fall into the seat. And then suddenly, the wheelchair seemed like a total liberation.

I remember I started zooming around the corridors and they told me to slow it down a bit, because I was overdoing it

That was when I started seeing the world again for the first time. It was the first time I’d seen the outside world for two and a half months. And I remember watching this woman [in the flats opposite the rehab unit] watering her flowers, and it was such an emotional moment for me. Just to see her doing that.

And I was thinking, at that point, “Oh, well, I’m a wheelchair person from now on. That’s alright, I know people in wheelchairs. I can do that. And maybe my sons can wheel me around a bit.”

And I actually texted Ade Adepitan, the TV presenter and Paralympian [who competed as an elite wheelchair basketball player], as we’d been in touch before, and I said “I might need some tips from you Ade, about how to do it.”

I think the idea of the wheelchair was really to get me out of bed and to give me mobility – and to allow me to be in the world more, because I probably underestimated the extent to which you can become totally institutionalised.

You lie there in bed and you have to ask “Can I have some water?” and it’s slightly pathetic. Whereas if you’re in a wheelchair, you’re able to go and get the water yourself. So that was part of the training – teaching you independence.

Because whatever state you’re going to leave in, they want you to be as independent as possible. And rather than having to wait for help, with the wheelchair you can often help yourself.

I was also able to lever myself from the wheelchair onto an exercise bike, which was a low, sitting down one, and I would sit there pumping away whilst I watched telly. And I loved that. It felt very good.

And what was the next milestone for you, in terms of your recovery?

The next stage was walking with a stick – which was amazing, as again, I felt very liberated by that. They gave me lovely routines and chants to remember, like “Nose over toes” and “Stick-foot-foot-stick” and I was then able to go to the gym and do activities like throwing balloons, kicking footballs and walking along the parallel bars.

Throwing a balloon was such a huge thing. It felt like throwing a lead weight, because I literally had no stomach muscles – they’d just gone completely. So after each throw I would wince and go “Aghhhh”.

The therapists, Emma and Ashima, would take me through all these routines and once I remember having a lovely conversation with Ashima where I said to her – and I didn’t mean this in a bad way, far from it – but I asked, “What sort of training did you have to do to do this?” and she said, very quietly and modestly, “I’ve got an MSc”. And I said, “Wow”.

And the reason I said “Wow” wasn’t because I had underestimated what she knew, it was because I was struck by how wonderful it was that here was someone with all this training, and all this skill and all this knowledge – and all of it was being funnelled down into such simple things for me to do.

And that was a great incentive to me too, because I thought “This is an incredible gift that they are giving you”.

I could see that everything they were asking me to do was about moving around the different muscle blocks in my body, and finding ways for me to develop resistance against the floor and so on.

And each time I went to the gym, something new would happen. I mean, in terms of progress, it was just stunning.

Now, if someone were to ask me something like “Michael, what do you consider to be one of your greatest achievements?”

I would say "Learning how to walk again after I was ill". I mean, I’ve done lots of things in my life – I’ve got qualifications and I’ve written books and all sorts of things.

But actually, at the moment, what I feel most proud of is the fact that I – well, it wasn’t me on my own, because that would be just daft – it’s the fact that we, working together, managed to go from me lying prone, helpless and weak to me walking around and even running. That feels to me like an amazing achievement.

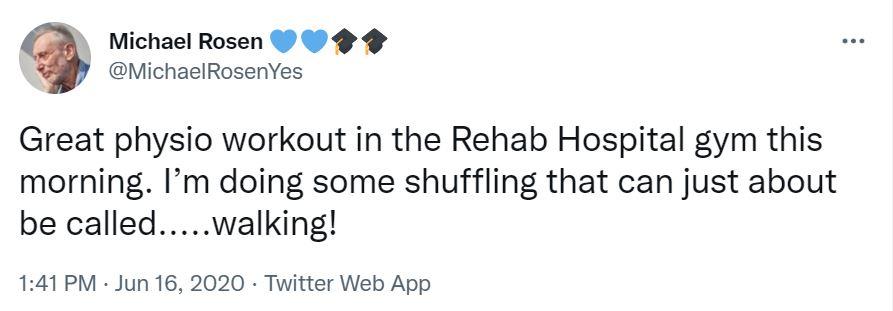

And then you had to learn to walk without using the stick?

Yes. One day one of the team came in and said, “I think you’ve become stick reliant”. And I remember laughing because I thought it was such a funny phrase, and I thought, “Well, yes, I do like my stick. I’m enjoying it and the fact that I can get about with it”.

But I guess my legs were now strong enough to have a go at walking without it. And that was the really scary bit. Partly because of the deconditioning, but also because of the lasting damage I had from Covid.

I can’t really see with my left eye anymore, or hear with my left ear, so I am a bit lopsided. And because of the low blood pressure, which was also caused by Covid, I now get a bit dizzy sometimes.

So you can imagine how unstable I felt when they said “Throw away the stick, Michael”. And there was this wonderful nurse called Doreen who was quite often enlisted to be the person to catch me!

How did you feel when you finally managed to start walking unaided again?

Well, my wife Emma had arranged to come to the gym and sit on the other side, because of Covid restrictions. And the day before she came, I managed to walk the whole length of the gym, which I guess was probably about 40-50 feet long, and I was immensely proud of this. So I was really looking forward to showing Emma that I could walk the entire length of the gym.

But then I started getting nervous about whether I would be able to do it again and I got a bit jumpy and nervy when she came in. I managed to get about halfway across and then started stumbling. I just couldn’t do it.

So I sat down on one of the benches and became quite upset. I felt that somehow or other maybe I’d never get there and I thought, at that stage, that I’d always be a bit of a stumbler and might only ever be able to walk for about a minute or so without feeling weak and exhausted.

Then, when I got to the point where I could walk up and down the corridor of the rehab hospital without stopping, it was heaven. I thought, “Wow, I’ve done it!”

And then, when I got home, I kept walking round the garden. And I remember thinking one day “Wow, I’ve shuffled round for 45 minutes”. So it was a great feeling. It was absolutely incredible.

Did you have more rehab at home, or within your local community?

Yes, when I came home, several physios came to see me. They asked me, “What are your long-term objectives?”

And I recall thinking, “Well, I’m 74-75, so I’m not sure if I really need to have any!” but then I thought “I’d quite like to get to the end of the street, and come back again without stopping, that would be good”. And they took notes on that and gave me advice.

And later on this very nice community physio, I think her name was Stephanie, came to visit me and she got me doing things around the front room. On one occasion, I had really bad pain on the inside of my knee – I think it was the medial ligament – and she gave me some lovely mini squats to do, and told me which exercises to avoid and which to do because she thought my iliotibial band needed stretching.

And since then I’ve been able to avoid any inside knee pain on my right leg at all, due to a combination of the way I now walk and the way I stretch. And that’s all thanks to Stephanie.

She came, I think three times and then she said I’d been doing well so she discharged me. It’s lovely, this phrase “discharge” because it sort of sounds like you’re disgraced – like you’ve been discharged from the army – but of course in medical terms it means you’ve gone up. Perhaps they ought to change it to graduate, “You’ve graduated!”. Anyway, it was a lovely thing to hear that she thought I was now okay – it was very encouraging.

And I told her I was taking regular walks round the park with my sons. As I described it, they now take “The Dad” for a walk instead of the dog – but I’ve reassured them that I won’t sniff any other dads.

Have you maintained an exercise regime since your rehab finished?

Yes. The community physio gave me some good exercises, which I’ve kept going on.

I do some of them when I’m out walking. I’ll stop and do some squats or whatever. And I’ve got mini weights to try to strengthen my upper frame and my core and I have one of those Thera bands, which I use while I’m sitting at the table and it’s a very easy way to stretch yourself.

I also try to walk every day to my office, which is a 30-minute walk from my home on the way there, and about a 40 minute walk back, because it’s up in Muswell Hill, near where we live.

I try to do that every day. And that’s a good old go for anyone my age, but particularly for somebody who’s been ill, so I’m quite proud of myself for doing that - and I carry a rucksack as well. I find that the walking is great, because you do a lot of inhalation and exhalation and you’re really using your lungs.

And I see a lot of old people – people of my age and older – where quite often it looks like it’s their legs that are the weakest.

Not walking is very debilitating. And walking is this fantastic thing that human beings have devised, because it’s different from the way the great apes move. It’s a very total exercise and it’s great for the mind as well. I mean, the ideas that I’ve come up with, since I’ve come out of hospital and started doing more walking. I tell you, I just write loads and loads now and a lot of the ideas occur while I’m walking.

So do you now feel back to normal, in terms of your creativity and work?

Yes. In fact, more so I think, if anything. I’ve expanded into areas that I wasn’t writing about before - to do with thinking about the mind in the body, and the body within the group and in society. Because we tend to separate all these things off, we think: “Oh, I’ve got a mind. But that’s nothing to do with my body, and my body has nothing to do with my mind, and my mind and body have nothing to do with anybody else. And they have nothing to do with society”.

And that’s all an illusion, because everything in our minds comes from society anyway. Although of course it feels personal. I mean, this language I’m using – I didn’t invent it – society did. And I only have to think about being nearly dead and now being alive. Well, my organism did some of that. But vast amounts of that happened due to this brilliant thing our society has created called the National Health Service.

So for me, coming out of a coma and learning how to live again has been a wonderful "me in the world” experience.

In Rastafarian language, they have this wonderful phrase “I and I”, which is this idea that your “I” is sort of attached to everybody else’s “I”. And it’s a brilliant phrase because “I and I” and all these other “I’s”, we’re all part of society.

We all have our own subjectivity. But we also have a shared identity, and my illness and recovery has helped me focus on that and really think it all through.

Do you have any advice for other people going through a similar period of rehab and recovery?

I think you have to be very, very self-motivated and try not to be self-pitying, or resistant to the help that’s offered.

And you have to learn to own your frailty. You can’t just say “Oh, well, I won’t bother to do anything, I’ll just wait until the physio turns up.”

You’ve got to say: “Right, this is me. I am weak. This is my body. I own my body. I’m now going to make it stronger. I’m going to get on the exercise bike and do the 30 or 40 minutes they told me I should do” and you’ve got to take all the advice on board and remember the phrases they tell you, and take responsibility so you can help yourself become independent. You have to own your frailty.

What would you like to say to all the physios and other healthcare staff who helped you and other Covid patients during the pandemic?

I’d like to say: Hello. My name is Michael Rosen. I was in a coma for 40 days. And it was you – the medical practitioners, the physiotherapists, the occupational therapists, the nurses – that got me out of that coma; got me to stand up; got me to take my first hesitant steps; helped me learn how to walk again and allowed me to get my strength back. It was all of you that enabled me to be here today. So I can’t even find the words to express my gratitude to you.

But more than that, my admiration, because I know the amount of training and thought and care that goes into all the work in your life. And I saw that at close quarters for myself during the three weeks I was in the rehabilitation hospital, and with the district and local care that I received from physiotherapists coming to see me at home. It’s all in my head now and I am forever grateful to you.

How we helped Michael recover

Emma Roussel and Ashima Sharma are part of the multidisciplinary team that provided Michael with rehabilitation at St Pancras Rehabilitation Unit, part of Central and North West London NHS Trust. Emma is a senior physiotherapist and Ashima is a senior occupational therapist.

What type of exercises and rehab did you get Michael to do, and how did these evolve over the course of his stay?

Emma: The rehab was very functional, guiding and practising the basic activities he needed to master to safely get back home – bed and chair transfers, personal care activities, standing and walking. As with many of our post Covid patients, we had to progress slowly and steadily, keeping a close eye on fatigue as well as on emotions. As Michael’s strength and exercise tolerance improved we were able to add in more challenging tasks, working on balance and progressing to more independent mobility.

Ashima: We’d ask him to practice getting in and out of bed, making himself a cup of tea or playing football within the parallel bars. That last one was important to him because he would play football in the garden with his son.

Did you work towards particular goals/functional aims with him?

Emma: We kept our focus on Michael’s goal of safely returning home to family, with short-term rehab targets naturally identified within that. Whilst we did talk about longer-term goals, it seemed that the acute experience of Covid made this quite challenging emotionally. So we focused on remaining positive and open-minded as we worked towards shorter-term functional goals. It’s fantastic now to see Michael has been able to return to some of his previous activities and roles that, at the time, he was unsure would be a possibility for him again.

Ashima: His main goal was to be able to return home walking, which we broke down into smaller achievable goals because, for Michael, that goal was daunting.

It sounds like you have a very multidisciplinary team approach to providing rehab - why do you think that works well and how does it benefit patients like Michael?

Emma: We are lucky in the rehab unit to have a very close team of therapists, including our physios, occupational therapists, rehabilitation assistants, speech and language therapists and our neuropsychologist.

We work directly alongside our brilliant nurses, healthcare assistants and the doctors. There is a lot of multidisciplinary discussion throughout an individual’s stay, so their rehab journey is guided and influenced by a range of experienced professionals but streamlined to common goals through effective communication and teamwork.

Ashima: It works because it means that we can have that 24/7 rehab approach to patients, and as a team we can focus on getting the patient independent in every area, not only on the mobility side of things but also for example, in terms of taking their own medications, personal care and hygiene.

Alongside the physical rehab, it sounds like your team helped to boost Michael’s mental wellbeing and his confidence in his own recovery.

Emma: I think an important aspect of our role as rehabilitation therapists is understanding someone’s anxieties and worries, and supporting them to gain the confidence to safely take that next step. Sometimes the small steps can be hugely important and empowering for an individual, and sometimes it is about helping someone to mentally take that step rather than physically.

Were you pleased with the progress he made whilst with you?

Emma: Michael worked really hard, despite the ongoing difficulties he was experiencing with his eyesight, hearing, fatigue and the emotional side of his recovery. He was always game for the next challenge, whether big or small. It was very rewarding to see and hear him express his sense of achievement as he progressed.

Ashima: Massively. We were all able to see the progress when we took Michael on his home visit and we saw that he could walk around his home on his own.

For someone to go from barely being able to stand without help and feeling very dizzy to then walking independently with a walking stick is amazing!

How did you feel about Michael dedicating his latest book to the care you provided and to all the staff who helped him learn to stand and walk again?

Emma: It is a privilege to hear Michael’s words describing his time on the rehab unit, as it gives a real insight into the patient’s perspective. It’s brilliant for the rehab team, and for the AHP professions, for Michael to share with the public, though his writing, his experience of the work we do.

Ashima: It’s great that Michael is doing what he loves again, especially because he had moments where he had felt that he might not be able to go back to it. I always see him raising awareness about the work that health care professionals do and it’s lovely to see.

Has your team been treating a lot of people who are recovering post-Covid?

Emma: On the rehab unit we have been seeing a number of post-Covid patients, as well as patients with secondary complications of Covid, for example stroke and neuropathies. We are also seeing many patients experiencing Long Covid within our community services.

Ashima: More so in the earlier parts of the pandemic. However, we still see patients who may have had Covid but also have a lot of other conditions which all together impact on their recovery.

What have you found to be the main challenges with Covid patients?

Emma: The wide-reaching impact of Covid on an individual physiologically, physically, emotionally and psychologically, makes the rehabilitation process complex. The significant effects on exercise tolerance, energy levels and fatigue present a particular challenge for rehab, but we know more now than we did 18 months ago about effectively managing this during the rehab process.

Ashima: Research is always changing, so making sure you’re up to date with the latest evidence so that you’re giving your patient the best possible chance to rehabilitate.

Number of subscribers: 1