This syndrome can be serious and can prompt legal claims if symptoms are misdiagnosed, say physios Laura Finucane, Chris Mercer and Sue Greenhalgh.

Cauda equina syndrome (CES) is a rare condition, occurring in one to three in every 100,000 people. Up to two people in every 100 with herniated lumbar discs may develop the condition. Without early interventions, the possible consequences can be devastating, including irreversible damage to bladder and bowel function, and sexual dysfunction.

Many patients seek help from a range of practitioners and delays in diagnosis can lead to long-term disabling consequences, resulting in costly negligence claims. The average cost of a CES claim is £336,000 (with about half this amount going to the patient). Delays are mainly caused by failures to recognise the signs and symptoms of the condition, delays in arranging MRI scans and delays in making referrals for surgical opinion.

For the best possible outcome, surgical decompression should take place as soon as practically possible, and within a few hours of the onset of symptoms. Current guidance tells us ‘nothing is to be gained by delaying surgery and much can be lost’ (Germon et al 2015).

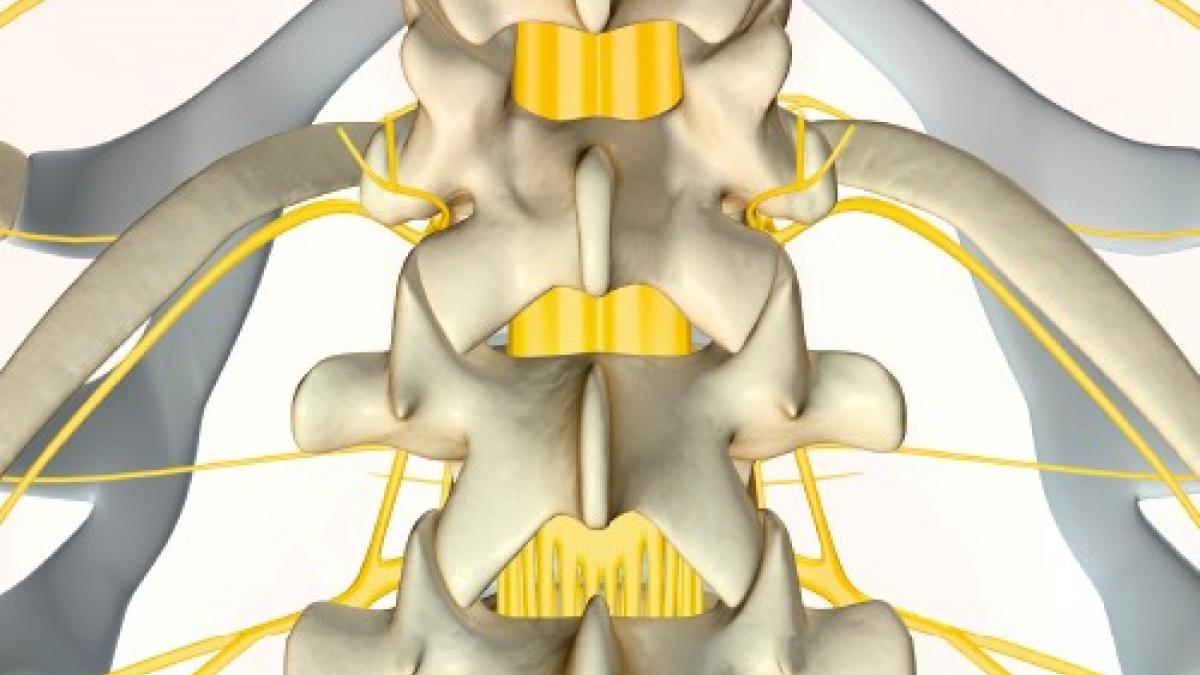

CES occurs when the nerves below the spinal cord are compressed, with the most common cause being a prolapsed lumbar spine disc. Other conditions such as spinal stenosis and metastatic spinal cord compression can also cause CES.

There is no agreed definition of CES but the British Association of Spinal Surgeons’ definition is useful in clinical practice. This states: ‘A patient presenting with acute back pain and/or leg pain with a suggestion of a disturbance of their bladder or bowel function and/or saddle sensory disturbance should be suspected of having a CES.’

We know that most of these patients will not have a critical compression of the cauda equina (about 10 per cent of people showing the signs and symptoms of CES actually have the condition). Despite this, physiotherapists should have a low threshold for requesting further investigations, such as an emergency scan or making a referral to A&E.

Sue Greenhalgh (co-author of this article), James Selfe, from Manchester Metropolitan University, and Valerie Webster, from Glasgow Caledonian University, have worked with people with CES to develop a toolkit to aid clinicians and patients in the early identification of CES. The toolkit includes a cue card to help clinicians ask the right questions during the examination. The credit card for patients contains information of what to look out for and what to do if patients develop symptoms

Good communication is vital as patients with suspected CES may not see the relevance of the questions clinicians put to them, especially if they are experiencing severe pain.

Examination

Anyone suspected of having CES must undergo a detailed subjective and physical examination. The examination should include a full neurological assessment, including sensation of the perineum to light touch and pin prick along with a digital rectal examination to assess anal tone. These tests should be carried out only by clinicians with the appropriate training and competence.

Clinicians seeing patients with potential CES must have clear and robust pathways of care in place to enable rapid onward referral when appropriate. All staff should be aware of these pathways.

- Laura Finucane, Chris Mercer and Sue Greenhalgh are consultant physios, at Sussex MSK Partnership, Western Sussex Hospitals NHS Trust and Bolton NHS Trust, respectively.

More information

- To download a copy of a CSP publication titled Learning from litigation: Cauda equina syndrome and view a CSP-commissioned video to help clinicians manage CES, see here.

- You can access the Cauda equina video titled Cauda Equina update here

Key characteristic features

The five key characteristic features of CES are consistently described in the literature and should form the basis of questions related to diagnosis:

- bilateral neurogenic sciatica

- reduced perineal sensation

- altered bladder function leading to painless retention

- loss of anal tone

- loss of sexual function

Key messages when CES is suspected

- communication – explain why you are asking these important questions.

- safety net – if you suspect a patient might be at risk of developing symptoms, tell them exactly how to respond if symptoms develop.

- documentation – record the time and date of consultation, your suspicion of CES, positive and negative findings, advice given, clinicians spoken to and at what time.

CES patient categories

Three groups of patients have been identified:

CESS – Suspected

Patients who do not have CES symptoms but who may go on to develop CES. It is important that patients understand the gravity of the condition and the importance of the time frame to seeking urgent medical attention. The use of a credit card-style patient information leaflet or a leaflet explaining what to look for and what to do should they develop symptoms is recommended.

CESI – Incomplete

Patients who present with urinary difficulties with a neurogenic origin, including loss of desire to void, poor stream, needing to strain to empty their bladder, and loss of urinary sensation. These patients could develop CESR and are a medical emergency and should be decompressed urgently.

CESR – Retention

Patients who present with painless urinary retention and overflow incontinence; the bladder is no longer under executive control. Surgical intervention is necessary and should be carried out as soon as practically possible.

References

- Germon T et al British Association of Spine Surgeons standards of care for cauda equina syndrome. The Spine Journal 2015;15 (3):2-S4.

- Greenhalgh S et al An investigation into the patient experience of cauda equina syndrome: A qualitative study. Physiotherapy Practice and Research 2015;36:23-31.

- Greenhalgh S et al Development of a toolkit for early identification of cauda equina syndrome. Primary Health Care Research & Development 2016;17(6):559-567.

- Todd NV and Dickson RA Standards of care in cauda equina syndrome. British Journal of Neurosurgery 2016;30(5):518-522.

- Wilson-MacDonald J Cauda equina syndrome and litigation. Orthopaedic Proceedings. Accessed 27.01.2017.

Authors:

Laura Finucane, Chris Mercer and Sue Greenhalgh are consultant physios, at Sussex MSK Partnership, Western Sussex Hospitals NHS Trust and Bolton NHS Trust

Number of subscribers: 6