More children are complaining of pain, but physiotherapists and colleagues can help them to manage, reduce and even get rid of it. Andrew Cole reports.

Pain can be acute or chronic, nagging or all-consuming. But handling it successfully poses challenges to all healthcare professionals, including physios – especially when the patient is a child or adolescent. The problem seems to be on the rise.

Advanced physiotherapist Jane Robinson says she has seen big increases in the number of referrals to the paediatric pain management service in Sheffield, from both hospital and community sectors. When she joined the outpatient service in 2009, it was receiving 100 new referrals a year. By 2014 the number had doubled – and the referrals continue to rise. A major factor, in her view, is the growing social pressure children are under. ‘Schools – and especially exams – are a massive stress factor. And then there is the whole impact of social media.’ This can manifest as chronic pain.

Ms Robinson and her colleagues encounter many children with widespread and non-specific pain. Some complain of abdominal pain, headaches or migraine and facial pain. Musculoskeletal pain is also common, especially lower or upper limb pain and back pain. In some cases, there is an underlying condition requiring medical treatment. Often the pain is inextricably connected to mental health problems. And then there may be family difficulties that need to be tackled before the child can be treated successfully.

On occasion, the ostensible physical problem – such as a sprained ankle or simple fracture – seems relatively mild compared to the resultant pain. ‘Sometimes kids report pain that is disproportionate to what is organically going on in the body,’ says Ms Robinson.

In all cases, she says, the golden rule is to listen to the child and give credence to what they say. ‘You need to show you believe them. Even if [it] seems far-fetched, there is a truth in what they are telling you.’

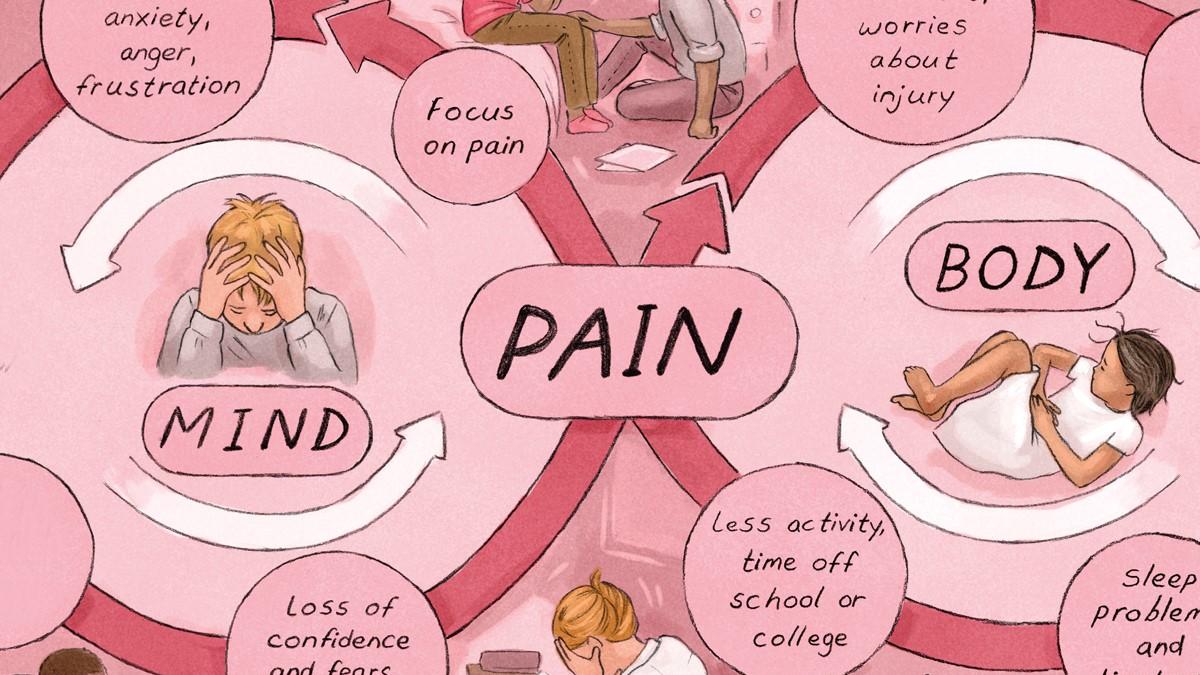

No matter whether there’s a psychological element to their perceived pain or not, it is important to recognise that the physical pain is real. ‘If the nervous system operates in an over-sensitive way it will start to interpret safe information as dangerous and therefore create pain.’

The Sheffield team does a lot of work teaching children how pain operates in order to help them take control of their own pain. It isn’t always possible to eliminate it but they can help the children to shift it to the background so they can get on with their lives. For many children this understanding can be transformative, says Ms Robinson. Although many still have some pain they report big differences in daily and family functioning, as well as in their development. The biggest improvement is in emotional functioning which ‘may reflect acknowledgement that their symptoms are believed and that someone is actually helping’.

Treating the 'whole family'

Physiotherapy and occupational therapy sit at the heart of the service’s multidisciplinary approach. After an initial physical assessment, the team will offer a tailored package, with probably nine out of 10 young patients referred to one of the therapists for an introduction to pain management.

Physical activation is often key to the children’s recovery. ‘Our skills as physios, such as exercise, massage and manual therapy, underpin that. But the wider skills come in how you then deliver that; how you develop the listening and psychological skills needed to get people to want to do those things, says Ms Robinson.’ Often that involves not just the child but the whole family.

Despite its prevalence, many physios do not feel confident dealing with chronic pain in children, says Ms Robinson. She is currently heading a working group at the Association of Paediatric Chartered Physiotherapists (APCP) that is designing a leaflet about pain management and is also looking at new ways of spreading the message through social media, study days and workshops. In her view there is much that paediatric physios can do when dealing with a child in pain (see guidelines on left and right).

‘Equally, it is important to know the limits to their competence. ‘Recognise what the limitations are to your service but don’t think you haven’t anything. But you also need to know there are specialist services out there and they are very happy to give advice.’

Problems can arise, she suggests, when physios are under such pressure that they don’t have time for in-depth consultations. ‘Generally we have very good communication skills. But if you’re in a service where appointments are restricted to 20 minutes and it can take 15 minutes to settle the child and their carer, you can see how that pressure to deliver can affect things.’

Chronic fatigue syndrome

One condition that often presents with a range of chronic pain symptoms is chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) or myalgic encephalopathy (ME), which affects at least one per cent of British secondary pupils.

According to a 2015 study of children and adolescents in the UK and the Netherlands, around three quarters of those with these conditions complain of muscle pains and/or headaches while well over half report sore throats, joint pains and/or long-lasting flu-like symptoms. See here for more information.

The children’s CFS/ME service at Royal United Hospitals Bath NHS Trust uses a range of techniques to help patients recover, including activity management, cognitive behaviour therapy and graded exercise therapy. The overall aim being to enable children to manage and control their pain.

‘We don’t promise to eliminate the pain but with specialist support it’s important to try to help the patient reach their goals and regain the social activities they were doing before,’ says specialist paediatric physiotherapist Joanne Bond-Kendall. ‘It’s about acknowledging what they’re feeling and then deciding jointly with the young person and parent or carer what the main problems are and then it’s how you design your treatment programme.’

It seems likely that physiotherapists will increasingly encounter children with CFS. Ms Bond-Kendall is particularly concerned about community physios who may be managing these patients in relative isolation. She urges physios to talk to colleagues and ask for advice where needed. Bath’s CFS/ME service is happy to provide help and support (ruh-tr.paedscfsme@nhs.net).

So do paediatric physiotherapists need more training in helping to manage children’s pain? The British Psychological Society’s guidelines (summarised in the two boxes) on managing invasive or distressing procedures suggest that they do, noting that the current situation is ‘variable’ (see ‘More information’ box for link to source).

Association of Paediatric Chartered Physiotherapists chair Michelle Baylis agrees there may be a need for specialist training when dealing with paediatric pain in a specific service. ‘But the exploration of pain within all areas of paediatric physiotherapy comes when you draw on the more basic skills of physiotherapy training,’ she says.

Avoiding distress and pain: British Psychological Society guidelines

- Be aware that the more negative the experience for the child, the greater the subsequent anxiety, distress and lack of co-operation

- Try to create the right environment for a procedure. Avoid disturbances and keep numbers to a minimum.

- Use techniques such as relaxation, distraction, guided imagery and graded exposure. Communication needs to be simple but honest. Look for non-verbal cues

- Allow children to participate as much as practicable – give permission to cry or shout

- Encourage the active participation of the child’s parents or carers – outcomes tend to be better when parents are present

- If a problem arises, take a break. Consider whether the procedure could be postponed. If not, you may need to consider sedation or even, briefly, restraint – according to agreed guidelines

- Afterwards, document what has been tried and what worked well. Consider lessons for future procedures and, if there has been a problem, look at whether team members might benefit from debriefing or further training.

Tips on handling children’s pain

- Listen carefully to the young person’s story and believe what they say. Acknowledge the pain they report and don’t dismiss it because it appears to be disproportionate

- Try to explain how pain works – and how this can have a knock-on effect on mood, fitness and activity levels

- Be patient. Activity baselines will need to be lower for children with chronic pain and the steps to increase activity smaller

- The overall aim is to achieve functional recovery where the child can do the things they want to, despite some pain. Eliminating the pain may not be possible

- Know the limits of your competence. Don’t be afraid to seek specialist help or refer a case on if you don’t have the skills to deal with it

Further reading

- British Psychological Society Good practice guidelines: Evidence-based guidelines for the management of invasive and/or distressing procedures with children.

- Sheffield Children’s NHS Trust pain management team. Tel: 0114 2717 397

- Association of Paediatric Chartered Physiotherapists (a CSP professional network)

Author

Andrew ColeNumber of subscribers: 3