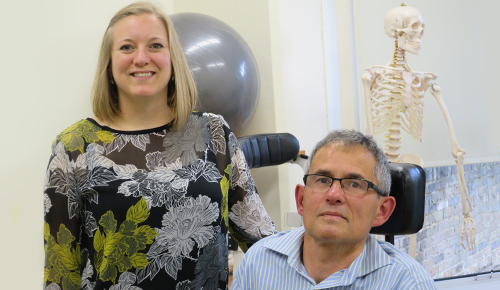

A physio and an occupational therapist identified a huge need for better neurological care. Does the centre they created offer a national model, asks Gill Hitchcock.

It’s a rainy day in Twickenham, west London. But the weather isn’t deterring members of a local Parkinson’s support group from joining their fortnightly session at Integrated Neurological Services. Known locally as INS, the charity was founded in 1993 by physiotherapist Ellie Kinnear and occupational therapist (OT) Liz Grove.

Janet Skeen finds the group stimulating. Noelle Dyer says it’s a lifesaver. For Jim O’Donoghue it’s a chance to talk about the issues he faces and know he’ll be understood. ‘It’s the only time when you can be honest about how you’re feeling, and everyone understands where you are coming from, which is a great relief,’ he says.

John Freed joined the group nine years ago, soon after he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s. He says he has received very little support from the NHS: ‘The GP doesn’t really want to know. The neurologist is very nice, very good, but he doesn’t really believe in exercise. He’s one of the old school.’

Ongoing support

Facilitating the group is physiotherapist Mandy Peake. The role is part of her work with a multidisciplinary team of neuro-physiotherapists, OTs, speech therapists, counsellors and social workers at INS.

The service started life in a church hall and now operates from a large converted house with a well-equipped gym, exercise spaces and meeting rooms. Although the therapeutic interventions are not particularly unusual or novel, Ms Peake says INS picks up where the NHS leaves off.

She believes the health service is good at acute care, less so when a patient’s condition plateaus.

Physiotherapist Jo Jethwa says that, unlike the NHS, groups for people with specific neurological conditions are organised around the needs of the clients, not a set of guidelines.

INS offers one-to-one therapy and an ‘expanded horizons’ programme of activities ranging across crafts, music therapy, cookery, computing and art.

‘Some of the clients did horse riding in the summer and they’ve now taken it up because they realised they can do it,’ says Ms Jethwa.

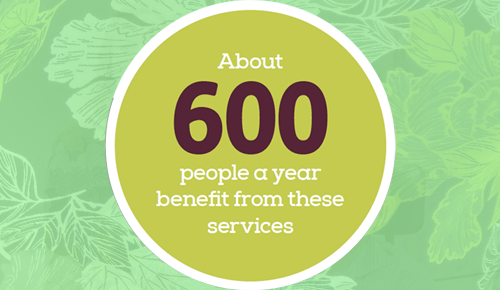

About 600 people a year benefit from these services. Craig Mundy, who has Parkinson’s and ataxia, visits INS at least once a week. He’s joined the gardening, iPad and memory groups and says they are a lot of fun.

This afternoon he and his physio Ms Jethwa are in the gym working on his strength and balance. ‘Six months ago I was in hospital for three weeks and when I came out I was stymied. I couldn’t walk, or stand, because after three weeks you lose balance and muscle strength, a tremendous amount,’ he says.

The services at INS are evaluated individually through client and carer feedback, and collectively through group discussions around current activities and future developments. Staff also use standard outcome measures.

The charity’s clinical manager and physiotherapist Carol Hopkins says, however, that it struggles to measure long-term input with clients in ways which are meaningful both to them and the organisation.

‘We have been using standard quality of life measures on an annual basis to see if they’re sensitive enough to the positive change that people are making,’ she says.

Greater control

Could this service provide a national model? One of the priorities in NHS England’s Five year forward view is giving people far greater control of their own care. The Berwick report on patient safety says that safe and effective care can only be achieved when patients are ‘powerful and involved at all levels’.

But a report by the King’s Fund last November found that 20 years after politicians and senior policymakers starting calling for patients to have a stronger voice about their care, improvement has been scant.

And then there’s the Better care fund. The innovative programme to integrate local health in England has been slated by the National Audit Office for poor planning and falling short on predicted cost savings to the tune of £700 million.

Margaret Hodge, chair of parliament’s public accounts committee, branded it a ‘shambles’.

INS staff agree that it would be wonderful to replicate their service. They also think that as a small organisation INS has the flexibility to respond quickly in adapting to people’s needs.

Ms Hopkins talks about the close links it has built with colleagues in the NHS – including neuro-rehabilitation teams and nurse specialists – social services and other third-sector organisations.

‘If you’re looking to reproduce the same model in other parts of the UK, you are going to have to build those links; you can’t just deposit little INSes around the country,’ she says.

Ann Bond, the chief executive of INS, thinks that the ‘fascinating thing’ about the service is that it has been integrated across health and social care from the very start: ‘So our model of having social workers, as well as therapists working together, supporting the family network, bridging that gap across social services, health and public health, has been something we have been very experienced in for the past 20 years.’

She doubts that a federated or franchise model would work, but says that the complexities of scaling-up could be overcome, provided a multidisciplinary team is there to support people responsively and a personalised approach is maintained.

Partnership working

And Ms Bond believes the NHS could learn from INS’s collaboration and partnership working. One example is the ‘insight group’ of clients and carers from the different types of groups or support services who meet quarterly with staff.

She describes this as a ‘melting pot’. People bring ideas, highlighting any gaps in the service and talk about what they want to do differently.

‘I think it would be a great to wake up one day and someone to have said, “A fantastic model, if you can replicate this elsewhere, we would love to pilot it.” I would be more than happy to go and seed this in any other part of the UK, with the right funding.’

Funding comes in from a range of sources. There are contracts with the London boroughs of Richmond and Hounslow, plus clinical commissioning groups in Hounslow, for specific services. These were worth nearly £500,000 last year.

INS also relies on donations, legacies and fundraising. But a Big Lottery grant of £86,600 – an ‘absolute cornerstone’, according to Ms Bond – runs out this year. She is working on a fresh bid, putting together ideas which might be attractive.

‘I would love to have some sustainable funding,’ says Ms Bond. ‘We have always said we would like some funding that underpins the organisation to give it stability and enable us to move forward effectively. But we don’t want full funding, because I think that would remove the autonomy that the clients and carers can have about shaping it.’

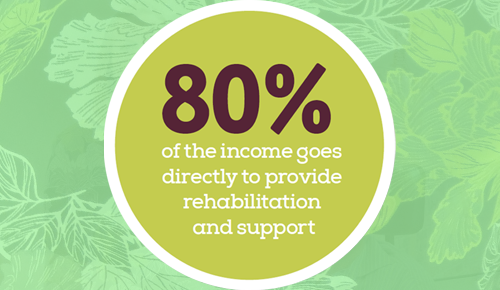

All of its income – totalling £977,000 in 2013-14 – is spent on service delivery. About 80 per cent goes directly to provide rehabilitation and support, with the remainder paying for running costs, such as premises and communications.

Survival rate

Ms Bond talks about the massive rise in the number of people being diagnosed with Parkinson’s, and the fantastic success of stroke services which has resulted in a 50 per cent rise in the survival rate.

So the need for the type of service that INS provides is growing. And the organisation needs to plan so it can support people over the coming five to 10 years.

Ms Jethra has a couple of friends with multiple sclerosis who desperately need something like INS. Unfortunately for them, they live outside its catchment area. Her firm belief is that it’s the right of every individual with a long-term complex condition to have this type of supportive service.

The people in the Parkinson’s group agree. Janet Skeen says there should be an INS in every place. She is shocked that people on other parts of the country don’t have the same opportunities.

‘We are very fortunate that we live in the Richmond or Hounslow boroughs,’ says John Freed. ‘If you are going to get Parkinson’s, get it here.’

Links

Author

Gill HitchcockNumber of subscribers: 1